What is the significance of UOO and GPC in the context of digital privacy and consumer rights.

Universal Opt Out (Mechanism) (UOO(M)) is not configured per website, but is a standardized signal sent to all visited websites from a browser. Universal Opt Out Mechanism(s) include GPC and will likely include similar technologies in future.

Global Privacy Control (GPC)1 is a browser setting indicating a user’s preferences regarding the collection, distribution, and sale of the user’s data. It is HTTP or HTTPS signal, transmitted over the DOM (Document Object Model) (GitHub, 2024). It is specific to web browsers and HTTP protocols; meaning it is for internet browsers and does not apply to IoT, or other methods of data collection. GPC must be flagged on each browser used; If a user surfs with GPC on in Firefox, but later that day goes to the same site in another browser, the new browser will also need to be set to the users’ preferences.

The future of UOOM will likely include other mechanism and services and expand past just HTTP. UOOM has room to grow to encompass multiple signals; GPC for HTTP(s), and other mechanisms for mobile devices, IoT, perhaps even ISP’s. As the IoT and information flow continues to grow, so too will the need for the toolsets and regulations.

Legal & Regulatory Framework

One of the key components in many of the USA laws is the narrowing of the term processing. For example, Colorado’s new law allows users to opt out of possessing “to advertising and sale…”2 (Rule 1.01, CCR 904-3) (Colorado Attorney General , 2021). California also focuses on the “Consumers’ Right to Opt Out of Sale or Sharing…”3 (California Privacy Protection Agency, 2020). The proposed New York law in the assembly focuses on, targeted advertising, sale, and profiling4. (New York Assembly, 2024)

Interestingly California, Colorado, and the GDPR (EU) all recognize and use the GPC HTTP signal in their laws, and New York’s proposal requires the acceptance of any type of opt out signal from multiple types of devices (leaving the door open for new UOOM).

Support

Focusing on the California Privacy Rights Act is a good place to start because it is the most populous state in the union, and represents the the largest tech industry.

The California AG lawsuit against Sephora proved that the state is willing to enforce those rules.

The mandate for opting out seems clear on the surface, yet different entities are defining “sale” differently- and the suit against Sephora helped clarify that sale doesn’t have to include financial transaction. In California law Sale of data means making available “to a third party for monetary or other valuable consideration.”5 (like rewards programs, or supplying to a service provider). A Browser with that signal turned on has not only opted out of collection, distribution, and sale of their data; but the responsibility of the data collector (in this case Sephora) does not stop at the point of turning on the signal. The collector must not share/distribute, and by that they must but make clear to service providers that the user of that data has opted out and the data is not available, should not be collected, and cannot be part of the transaction.6 (Office of Attorney General, San Francisco Superior Court, 2022)

Do Consumers Have Control of Their Data?

Sadly, no, UOOM and GPC are not the end game. UOOM and GPC are the very beginning, and necessary to start the conversation of opting out of data collection and sale.

Currently the UOOM and GPC is specific to HTTP – and it is browser driven. A regular person may surf using Chrome (where GPC isn’t default & requires an addon) or Firefox(where GPC is default if in “Incognito mode”) – but if they switch to edge, or their phone, the GPC flag may not be there.

From watching videos of the Colorado AG and other law officials discuss GPC7, there are also mis-understandings and misconceptions about how a user is identified on the web. Some arguing that the user’s data isn’t collected till passing a sign in wall. Faulty understanding of the technology can lead to faulty assumptions and make enforcement impossible- for example, if the people drafting or enforcing the law don’t understand or agree on an identifier, how can protection be enacted and enforced?

For consumers it will offer an incomplete understanding of privacy. Selecting or opting to turn it on, is removed when you dump your cache, and you have to do it again. GPC doesn’t carry across browsers, or devices. Even if the company knows it’s you, and you have signed in, and you opted out of tracking in Firefox- if you log in using another device, you are not sending the opt out signal. How companies choose to collect when a user has opted out, but navigated using a different tool – has not been settled, and is not part of the laws.

Privacy settings on HTTP(s) are a great starting point, and it is exciting to be moving in the right direction. However GPC reflects only a small fraction of the consumer data that is tracked and monetized. Consider the report by the FTC in October of 2021, regarding the privacy practices of six of our major Internet Service Providers. (Federal Trade Commission, 2021)

What Are Some Conflicts Between UooM and Convenience?

Access to Information Friction Points

Currently, because UOOM is not across all states, nor is it adopted across platforms, there are still sites that will prevent viewing if you don’t allow their cookies. In those instances, individuals could be blocked from information.

Companies, that don’t need to sell data to make money with your data, won’t feel any issue with it. But smaller companies may find acquiring data for their projects more difficult. Will the price for the sale of data go up, (from ISPs, or other data sources) when they have less competition. Will this make it less competitive and harder for younger startups and innovation??

Privacy V. Convenience

As for privacy v convenience, there isn’t much to say there. This is an initial step to grant some controls, and reduction of transmission of some data. Data continues to be collected from non-flagged browsers and non HTPP sources.

The convenience of the selection is a great first step, and a distinct improvement over opting out at each site. Clarity on the GPC and its limitations needs to be clearer in the support documentation on the different browsers.

Example WaPo

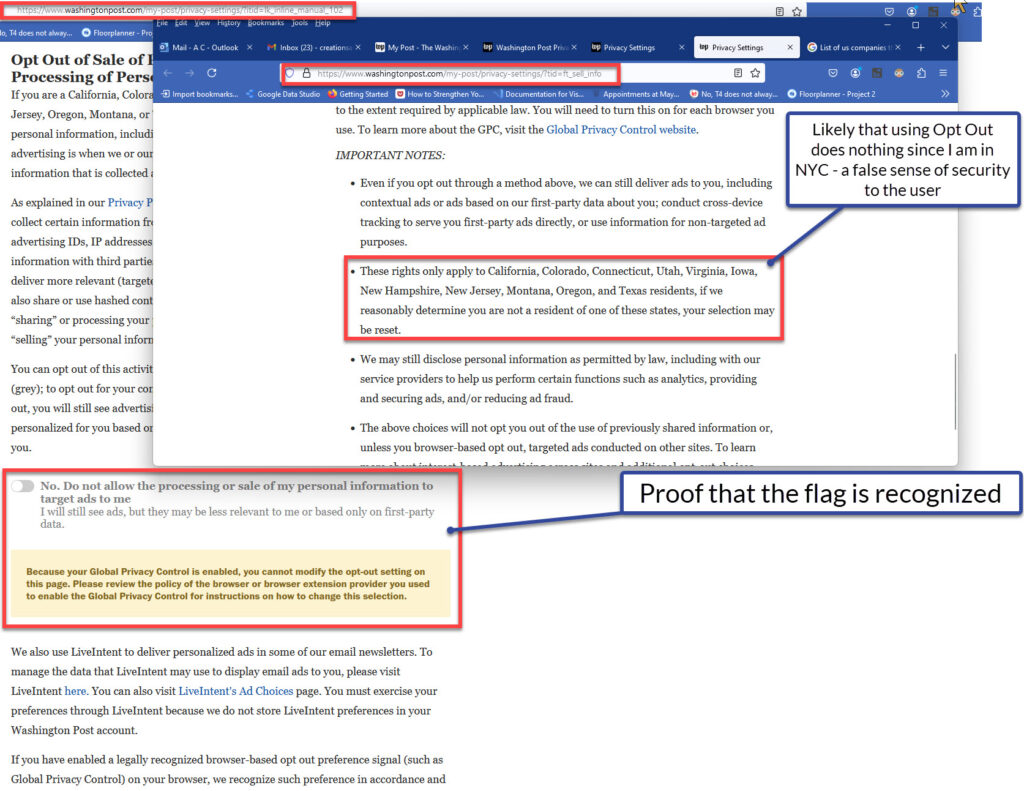

Washington Post appears to have used and accepted Universal Opt Out as a marketing tool. They are listed in the GPC site, yet on the WP privacy documents it is clear that they will segregate, and disregard the GPC if your IP or any other information indicates you are in a location where GPC is not required by law.

The WP looks good on the GPC Founding Organizations page, while actively striving to do the bare minimum. WP also strongly encourage the use of their apps by limiting browser functionality on mobile devices, while their Privacy Policy8 makes clear they gather data on “…sites, mobile and tablet apps and other online products and services…”9. (Washington Post, 2024)

Using Firefox Incognito (GPC is automatic) I navigated from the Privacy Statement to the Your Privacy Choices page, it is evident that GPC opt out is flag is received. That same page indicates if you don’t reside in the states where that is enforced, your privacy may be reset. Weather they do or not, is unclear, but with their verbiage and the amount of time to write these documents, it is likely that users location sets an automation to allow the tracking and selling if outside of the areas where it is required by law.

Monetizing data appears to be important enough to make these marketing decisions.

Increase Awareness

Currently it is only people who already care, that search and find out about privacy.

Awareness is increased when there are pushes on legislation through links and mentions on the news media. I don’t know how to make it “sexy”, but perhaps early education and exercises could increase awareness amongst the young, and their parents/caregivers.

Support Materials & Website Improvements

There are basic absences on all of the sites regarding privacy and GPC, such as:

- Simplified explanations,

- Quick start guides, and

- Why some cookies are necessary.

- What a third party is, and

- why it matters.

Essentially, to try to get the interest and information out, advocates must fight the noise of the endless information pollution. If the Colorado or California AG had influencer contacts, that could be a point to leverage.

However, there is nothing to leverage if simplified support materials are not available. If they leveraged an influencer now, and directed to their websites – any campaign would fail because the information provided is poorly developed for lay persons, and isn’t available in multiple languages.

The closest I can get to marketing, is to suggest: Simplify, sexify, amplify.

Future of Uoo & Privacy Enhancing Tech

The GPC as a UOOM tool is a fantastic start. I would hope it is only a start, and privacy advocates, and technologists would work together to explore the other areas that need addressing. In fact, starting small, like the GPC may be exactly the right start – if advocates can amplify the discussion of it’s value, and create stories of success. Those same stories can then be leveraged to ease progression and deployment of the next tool. I suspect it is easiest to develop the laws and tools in this process from smallest to largest: from HTTP(s) to Mobile to IoT, tracking across devices, and eventually to IP. This enables the defining of terms, that can then be used in the next stage, and allows the time and space for measurement of success. Once we have some established rules and mechanisms for privacy rights, we can explore what that means with regards to AI. We cannot establish rules around AI specific to privacy rights, prior to having some rules about privacy rights.

However, I do hope that the process is already begun; inertia is a battle that is regularly lost.

Policy Recommendations

I think one of the key components that must be done to enhance UOOM, is to incorporate the right to be forgotten into the rule making. While it is within GDPR, it is completely absent from the USA laws being developed and enacted.

The US laws are defining legal gathering and use of data to be “publicly available information.”

Consider in the draft of the American Privacy Rights Act of 202410 stating “publicly available information” is excluded from covered data §2(9)(B)(iii) (Senate & House of Representatives, 2024)

It defines Publicly Available Information to mean any information that “… has been lawfully made available to the general public…”§2(32)(A)

Yet in the supreme court decision of DOJ v. Reporters Comm. for Free of the press, 489 U.S. 749 (1989) (U.S. Supreme Court, 1989)

Page 763 states

“…To begin with, both the common law and the literal understandings of privacy encompass the individual’s control of information concerning his or her person. In an organized society, there are few facts that are not at one time or another divulged to another. [SCOTUS Footnote 14] Thus, the extent of the protection accorded a privacy right at common law rested in part on the degree of dissemination of the allegedly private fact and the extent to which the passage of time rendered it private. [ SCOTUS Footnote 15] According to Webster’s initial definition, information may be classified as “private” if it is “intended for or restricted to the use of a particular person or group or class of persons: not freely available to the public.”11

This would mean that just because it has been public (once upon a time) does not mean it is public now. The footnotes are very interesting and ties nicely with the Contextual Integrity heuristic; selective disclosure and fixing limits upon the publicity. Just because there is information on an individual attending university, it does not follow that that should be shared with that individual shopping service 30 years later.

Footnotes

- GPC Signal Definition defining a signal transmitted over HTTP and through the DOM, GitHub, March 22, 2024 ↩︎

- Rule 1.01 CCR 904-3 ↩︎

- California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, Amended in 2020, § 1798.120 ↩︎

- New York State Assembly. (2024) Bill S00365: An Act to Enact the New York Privacy Act § 1102.2 ↩︎

- California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, Amended in 2020, § 1798.140(ad)(1) ↩︎

- Filed Judgement – Office of the Attorney General, San Francisco County Superior Court, Aug 24, 2022 – the judgment & Sephora Settlement. Section 6 offers some clarity on the definition of Sale. Laymen’s terms of the same can be found at the same site, with the Press Release, Settlement Announcement, August 24, 2022. ↩︎

- Video list provided at the end of this document. Includes presentations by law offices discussing the Colorado and the California Privacy laws. ↩︎

- Washington Post Privacy Policy ↩︎

- Italics added for emphasis ↩︎

- 2024 American Privacy Rights Act (APRA), ↩︎

- DOJ v. Reporters Comm. For Free Press, 489 U.S. 749 (1989) pg -763 through 764 ↩︎

Videos

AG Colorado- Data Privacy and GPC Webinar Colorado office of Attorney General, Phil Weiser AG

CPRA Session 5 Universal Opt Outs and Global Privacy Control Sheri Porath Rockwell, California’s Lawyers Association, and Stacy Grey, Director of Legal Research and Analysis at Privacy Forum. Guest Speakers Dr. Rob van Eijk, EU managing Director, Future of Privacy Forum, and Tanvi Vyas, Principal Engineer at Mozilla

TEDx – Data Privacy and Consent | Fred Cate Fred Cate, VP for research at Indiana University, Distinguished Professor of Law at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, and Senior Fellow of the Center for Applied Cybersecurity Research.

Lessons Learned from California on Global Privacy Control Donna Frazier, SR VP of Privacy Initiatives at BBB National Programs and Jason Cronk, Chair and founder of the Institute of Operational Privacy Design.