I read an interesting article a while back, and am going to break down some concerns about probability and AI.

Both are critical to discuss as we roll forward into an untamed future where unregulated AI intersects with not just business practices, but the human condition, or even potential human existence. Here I’ll discusses the use of big data and AI to make decisions about life, without having the knowledge, regulation, or oversight to do it ethically.

An existential example of this absence is in the field of reproductive technology. AI is being used to evaluate a person’s life before birth. Polygenic screening within IVF treatments is a fascinating study of how unregulated AI, with incomplete data and opaque algorithms, is influencing deeply personal, and truly existential, decisions.

Unregulated IVF

On April 1, 2025, the New York Times published an opinion piece, IVF Gene Selection Fertility: Should Human Life be Optimized. It’s a fascinating article, starting with the genetic defect her mother suffered from, spurring her to start a genetic screening on embryos’ DNA for a variety of conditions. Starting with the emotional screening for a genetic switch for blindness, nearly seamlessly goes on to discuss polygenic screening – stating it’s a risk profile for conditions such as heart disease.

What is Polygenic Screening, Really?

To understand ethical concerns around polygenic embryo screening, we have to start with what these predictions are actually based on, and how fragile that foundation is.

Polygenic Risk Score (PRS)

Now, if you want to actually look up Polygenic Screening, you will want to search for Polygenic Risk Score (PRS). A PRS is the sum of the effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNP), which are small differences in a DNA sequence that vary from person to person. One SNP has minimal impact, but adding multiple together can produce what is called a Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) to allow for an estimate of individual condition risk1.

This means we are stacking thousands of tiny genetic differences to generate a profile. It’s probabilistic, not predictive; built on patterns, not certainties.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNP)

There are more than 10 million SNPs within the human genome, and when they interact with each other, they can have a variety of different outcomes, like height, tumor risk, or even psychiatric conditions. Because SNPs interact in complex ways, predicting outcomes is regularly uncertain. Stacking these millions of SNPs, their conditions, or mutations, can all alter and have effects on gene expressions; like how tall you are able to grow, your likelihood of having medical conditions, and more.

This is very exciting technology, a huge leap forward in the human understanding of how we are made, and how all our genes, stack to make us whole. But, it is in its infancy, and we have over 10 million SNPs. Consider if we had only 10 million independent SNPs, and each SNP had 2 possible alleles (version of a gene), then there is too large a possibility of combinations to even begin to fathom.

210,000,000 ≈ 103,010,299

While this formula is a simplification, the point remains: the sheer scale of genetic variation makes prediction practically impossible.

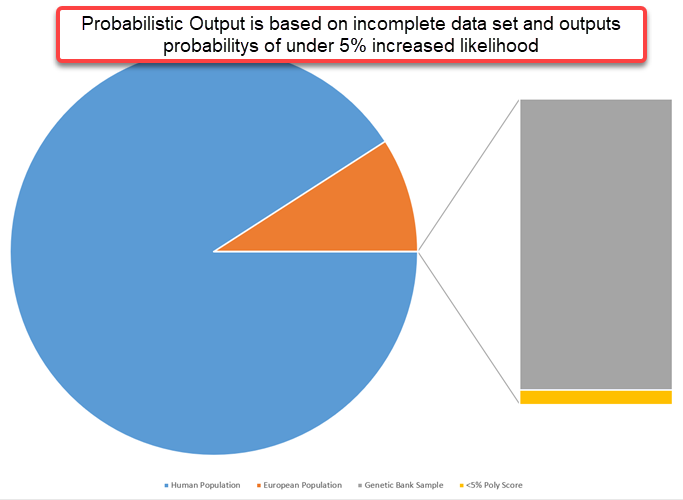

And here’s one more key data point: if you add together participants of three of the most comprehensive publicly available genome sequencing datasets, including gnomAD v4, UK Biobank, and 1000 Genomes project, they collectively represent only about .15% of the European population2. That means probabilities are being generated based on an incredibly small and incomplete dataset.

We Don’t Have All the Information Yet.

Clearly, a fundamental problem is that the data being used to build these predictive models is incomplete. SNPs come from limited datasets, and companies are using those incomplete samples to build statistical probabilities about complex human traits. The incomplete foundation makes the outputs, the “predictions”, fundamentally unreliable.

On top of that, the SNPs are then added and combined to create the PRS. This means that the risk score is a set of numbers from a non-complete data set, combining that to form relationships with other non-complete data sets, to predict complex human traits. Building predictions on incomplete datasets is foundationally unsound.

In a well cited paper Nature Genetics, Manuscript: Common SNPs explain article states “SNPs identified to date explain only ~5% of the phenotypic variance for height”3. Even for something as measurable as height, our best models still explain only a small fraction; the study used Human Height SNP because it was one of the most identifiable, quantifiable, and best understood SNPs to date. What does this imply about our ability to predict more complex traits?

If using an SNP for height is one of the most current, defined and understandable SNPs to date, we must accept that combining these even less defined and understood to aggregate a score for probabilities is risky at best – misleading at worst.

Carefully Selected as an Embryo

Returning to the NY Times article, Orchid is described as “… offering what is essentially a risk profile on each embryo’s propensity for conditions such as heart disease, for which the genetic component is far more complex.” This is a very simplified statement to explain the SNP and PRS as discussed above4.

The article also states Orchid can screen for conditions like obesity, autism, intellectual ability, and height. However, it glosses over a critical point: the United States has little to no regulation in the IVF field. These PRS-based screenings have made the U.S. a destination for global fertility patients, not because the science is more advanced, but because the regulatory barriers are fewer.

Today, Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT) is used in over half of all IVF procedures. Several American companies now offer PGT-P, which incorporates Polygenic Risk Scores. This is happening even though, in adults, the results of these scores remain ethically controversial and scientifically uncertain.

Most other countries have recognized concerns regarding PRS. Many have banned or strictly limited the use of non-medical predictive scores in IVF. Several European nations prohibit the use of polygenic embryo screening for traits like intelligence or psychiatric risk, citing ethical and scientific concerns5. In contrast, the lack of oversight in the United States has fueled a booming and largely unregulated market. It is a market driven by hope, but based on data that does not justify that level of confidence.

Big Data

Continuing with Orchid as our example, we know they run modeling techniques on both partners DNA to map inheritance patterns.

Advanced statistical models are used, but they add complexity and reduce transparency for the perspective parent. Unless the parent is already a geneticist, or a computer scientist, they are unlikely to understand Orchids description for Statistical Modeling6, including Monte Carlo simulations, Bayesian probability, recombination modeling and more, to predict embryo outcomes. These aren’t simple calculators, they are big data aggregators running probabilistic scenarios based on incomplete datasets. Their complexity challenges any principles of transparency and informed consent that we would want from responsible AI. The end of this hopeful future parents can get an embryo report, allowing them to make an informed decision about which embryo to prioritize for transfer. But, are they informed? Given the complexity of the models and the opacity of the language used to describe them, the answer is almost certainly no. Informed consent becomes nearly impossible under these conditions.

This entire process is built on large datasets and intricate modeling methodologies. It’s interesting, and promises all sorts of great things; but it is all probabilistic. Consider what it means to tell someone to select an embryo that is 50% less likely to develop schizophrenia, when the base risk for the condition is already under 1 percent, the prediction is drawn from data representing less than 0.15 percent of the population, and the models themselves have wide margins of uncertainty

The numbers may imply precision, but the science and data behind them does not.

AI Studies

Several recent studies highlight how artificial intelligence is being used to improve polygenic risk prediction.

- Deep Neural Networks have shown that they can improve estimation of polygenic risk scores for breast cancer.

- Non Linear Machine Learning Models incorporating SNPs and PRS improve polygenic prediction in diverse human populations.

- AI-based multi-PRS models outperform classical single-PRS models.

Aside from the excitement showing that AI can boost the performance of polygenic prediction, they are each using predictions that are best known and defined, such as height, breast cancer risk, cholesterol, etc. They didn’t each choose identical prediction sets, but they were within a set of well defined, best known combinations.

As discussed earlier, even for a trait like height, only about 5% of the variation we observe in people’s height can be explained by the SNPs identified so far. That means even the most advanced tools remain limited. Applying machine learning and AI to these best-known examples allows for more effective testing and training, which leads to more consistent outputs. This success does not automatically carry over to traits that are more complex or poorly understood.

Make no mistake, it’s incredibly exciting that some of the machine learning tools are capable of increasing the accuracy of probabilistic risk to have breast cancer, or high blood pressure, but it’s just a probability. These studies show AI can improve prediction slightly for well understood conditions, but the models are still dependent on incomplete data from small data groups7. The excitement around AI’s predictive power must be tempered by the reality that these are still just probabilities, not certainties.

Increasing probability is not the same as achieving accuracy, and when considering embryo selection, that distinction matters.

Responsible AI and Global Regulation

All of this brings us back to the ethical foundation of AI use. Responsible AI is supposed to be transparent, fair, inclusive, and accountable8. Yet the use of PRS in embryo selection in the U.S. is none of these. It is opaque, unregulated, built on incomplete data, and applied in deeply personal, high-stakes decisions.

By contrast, the European Union and United Kingdom have laws in place that prohibit the use of polygenic screening in IVF for non-medical traits or poorly validated conditions. They have drawn clear ethical boundaries that can be seen in multiple countries, and from multiple governing bodies.

Conclusion: Building the Tech, Ignoring the Guardrails

What we are seeing is a path of two futures: the U.S. builds the technology, while the EU builds the guardrails. Without urgent alignment between innovation and ethical governance, we risk letting unproven AI systems make decisions that shape human life before it even begins. This reflects a complete abdication of governance. As described in this paper, there is an unreasonable amount of information that a person would have to know, to be well enough informed to understand the use of these tools and what they mean.

Handing a person who wants to be a parent, a sheet of paper with predictions based on incomplete data, and then them choosing which life to pursue? This paper didn’t even begin to scrape the deeper ethical questions of what happens when that child isn’t the tallest, smartest, or what ever trait they were selected for? Do parents raise that child as if they purchased a pre made pizza, and wonder where the toppings they ordered are? Probabilistic outcomes on a human existence, being used to decide if one cell cluster is of greater value than another. The problems here lay much deeper than just the selection or avoidance of potential heart disease.

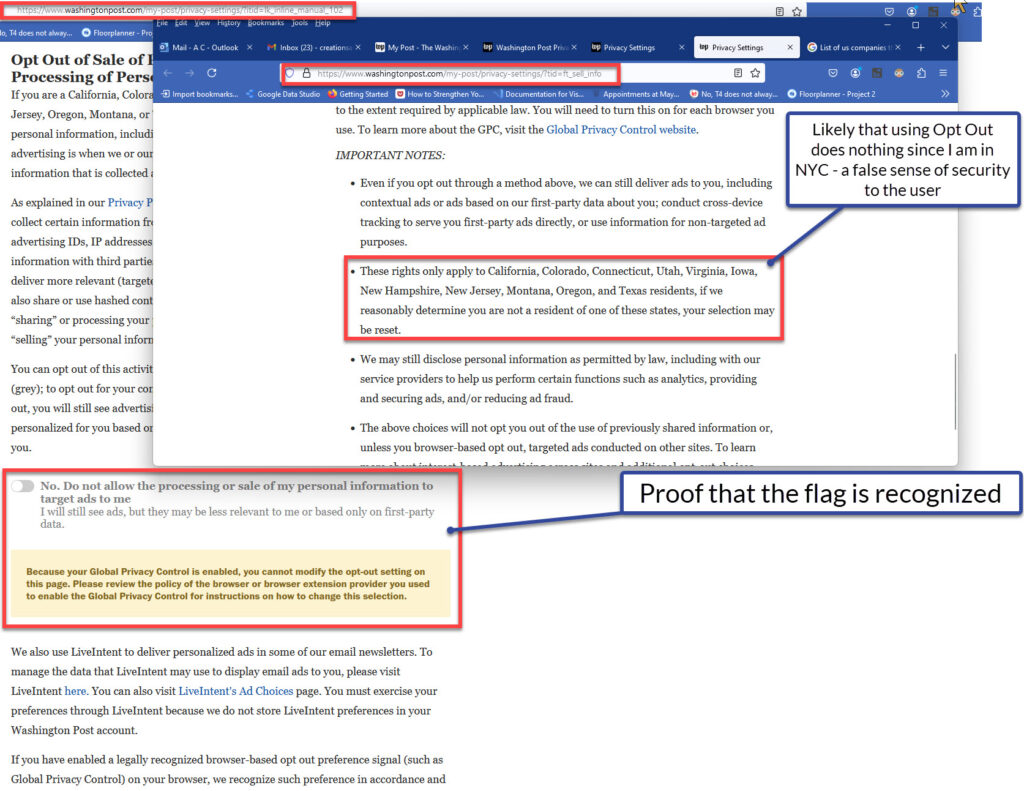

The USA stands out among the countries with advanced in vitro fertilization for its lack of regulations governing PGT-P. Often, its ethical and legal guardrails are shaped by international influences, like the GDPR inspired California and Colorado privacy laws. Here’s to hoping that the states start looking at their IVF industries, and start to explore how to support the future families.

At some point, we may reconsider whether what is being offered by these clinics is truly “probabilistic” at all. When the data behind these models is so limited, the output becomes less a scientific prediction and more a matter of hope. It is almost certain that legal teams have carefully worded disclaimers to avoid claims of certainty or guarantees, yet it may be inevitable that at some point, disappointed parents may decide that the probability of a lawsuit is worth pursuing.

Could the IVF clinics perhaps be curtailed from selling designer babies under false advertising or predatory practices? Nothing is decided, and I don’t have the answer. But I do think we should be asking these questions.

I look forward to watching and learning more as our future unfolds.

Footnotes

- Psychiatry at the Margins ↩︎

- Approximate Participant Counts in known genome projects that become part of the data lake: UK Biobank (500k), 1000 Genomes Project (2504), gnomAD v4 (800k). The estimated average participant of European descent was 95%, 24%, 83%. Estimate of European population 750 million. ↩︎

- National Library of Medicine | National Center for Biotechnology Information | Sizing up human height variation published in May 2008 and Common SNPs explain a large proportion of heritability for human height. These two articles go into great depths and details of the combining of SNPs as well as the fact that there is an average of 45% variance even when measuring SNP of the most recognized type (Height). They also highlight that SNPs (at current understanding) only account for a small fraction of genetic variation. ↩︎

- US Leadership in AI: P8 – States trust requires accuracy, reliability, explainability, objectivity, and more, the use of AI and probabilistic models for PGT-P is missing the mark. ↩︎

- In the UK the Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority (HFEA) prohibits the use of PGT-P for non medical purposes. Similar laws can be found in most of the EU member states as well. ↩︎

- Orchidhealth.com website page The Science Behind our GRS, they mention simulations, modeling patterns, statistical computing, and recombination. ↩︎

- Nature | Analysis of polygenic risk score usage and performance in diverse human populations. Most common data sets for PRS and SNPs are of white European descent (67%), East Asian (19%), and others in smaller quantities. ↩︎

- KPMG Trusted AI governance approach lists fairness, transparency, explainability, accountability, data integrity, reliability, security, safety, privacy, and sustainability as their principles within their pillars of KPMG Trusted AI. Using that same set of pillars, PRS-P lacks at least five of the ten. We haven’t reviewed the other five in this paper. ↩︎

References

References

Adrien Badre, L. Z. (2023, July 24). Arxiv | Quantitative Biology > Quantitative Methods | Deep neural network improves the estimation of polygenic risk scores for breast cancer. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.13010

Aftab, A. (2024, February 17). Psychatry at the Margins | Polygenic Embroy Screening and Schizophrenia. https://www.psychiatrymargins.com/p/polygenic-embryo-screening-and-schizophrenia

Biobank. (2025). Uk Biobank | QHole genome sequencing. https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research/about-our-data/genetic-data

Elgart, M., Lyons , G., Romero-Brufau, S., Kurniansyah, N., Brody, J. A., Guo, X., . . . Sofer, T. (2022, August 22). Communications Biology | Non-linear machine learning models incorporating SNPs and PRS improve polygenic prediction in diverse human populations. Retrieved from Communications biology: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-022-03812-z

Gabriel Lázaro-Muñoz, P. J. (2023, November 9). ELSI Hub | Screening Embroyos for Psychiatric Conditions: Public Perspectives, Ethical and Social Issues. https://elsihub.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/Screening%20Embryos%20for%20Psychiatric%20Conditions_Nov%202023%20version.pdf

Genet, N. (2011, December 6). National Library of Medicine | Common SNPs explain a large proportion of heritability for human height. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3232052/

Global Resilience Federation. (2023). The Leadership Guide to Securing AI. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60ccb2c6d4292542967cece7/t/64de2fcdedf2a93df1177eea/1692282832064/AI+Balancing+Act_DASDesign+FINAL_digital+Secured.pdf

Global Resilience Federation. (2025). Global Resilience Federation | AI Security. https://www.grf.org/ai-security

HHS. (Revised 2024, March 27). Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (‘Common Rule’). https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/common-rule/index.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority. (2025, April 15). Embryo testing and treatments for disease. https://www.hfea.gov.uk/treatments/embryo-testing-and-treatments-for-disease

IGSR: International Genome Sample Resource. (2025). How many individuals have been sequenced in IGSR projects. https://www.internationalgenome.org/faq/how-many-individuals-have-been-sequenced-in-igsr-projects-and-how-were-they-selected/

Jan Henric Klau, C. M. (2023, June 26). Frontiers | AI – based multi-PRS models outperform classical single-PRS models. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2023.1217860/full

Katherine Chao, g. P. (n.d.). gnomAD v4.0. https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/news/2023-11-gnomad-v4-0/

KPMG. (2023, December). KPMG Trusted Approach . https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmgsites/xx/pdf/2023/12/kpmg-trusted-ai-approach.pdf?v=latest

L. Duncan, H. S. (2019, July 25). Nature Communications | Analysis of polygenic risk score usage and performance in diverse human populations. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-11112-0

Logan, J. (2022, September 2). Mad in America | Genetic Embryo Screening for Psychiatric Risk Not Supported by Evidence, Ethically Questionable. Mad in America | Science, Psychiatry and Social Justice: https://www.madinamerica.com/2022/09/genetic-screening-ethically-questionable/

Merriam Webster Dictionary. (2025, May 4). Merriam Webster | Dictionary | Morals. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/morals

NIST. (2019, August 9). NIST | U.S. Leadership in AI: A Plan for Federal Engagement in Developing Technical Standards and Related Tools. https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2019/08/10/ai_standards_fedengagement_plan_9aug2019.pdf

OECD.AI and GPAI. (2025). OECD | Policies, data and analysis for trustworthy artificial intelligence. https://oecd.ai/en/

Sussman, A. L. (2025, April 01). Should Human Life Be Optimized. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/04/01/opinion/ivf-gene-selection-fertility.html

The White House. (2023, November 01). Federal Register | Safe, Secure, and Trustworth Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence | EO 14110. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/11/01/2023-24283/safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence

The White House. (2025, 01 31). Federal Register | Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence | EO 14179. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/31/2025-02172/removing-barriers-to-american-leadership-in-artificial-intelligence

Tom L. Beauchamp, J. F. (2009, 2013). Pinciples of Biomedical Ethics. Retrieved from Internet Archive | https://archive.org/details/principlesofbiom0000beau_k8c1/page/n5/mode/2up